In 1989 I visited the Argentine province of Misiones for the first time. Misiones is in the far northeast of the country, a finger of sub-tropical territory extending between Brazil (to the east and north) and Paraguay (to the west). The province is best known to the wider world for the amazing Iguazú Falls, which Argentina shares with Brazil. In the southeast of Misiones are the 17th-century ruins of the mission town – or reducción – of San Ignacio Miní, one of the many forced settlements of indigenous people that were established by the Jesuits in this part of South America. It is because of these missions that the province takes its name.

My primary reason for going to Misiones, however, was to visit Colonia Victoria, a former agricultural community that in 1933 was established for British settlers. By the time of my visit, there were no longer any British living in there, though faint traces of their presence did survive in the form of abandoned and tumbledown houses that were gradually being absorbed by the forest around.

My primary reason for going to Misiones, however, was to visit Colonia Victoria, a former agricultural community that in 1933 was established for British settlers. By the time of my visit, there were no longer any British living in there, though faint traces of their presence did survive in the form of abandoned and tumbledown houses that were gradually being absorbed by the forest around.

During my stay I met with the very few British immigrants who had stayed on in Misiones; by then, all were living in Eldorado, a town some ten kilometres south of Colonia Victoria and 100 kilometres south of Iguazú. Like Colonia Victoria, Eldorado was established by Adolf Julius Schwelm, a former banker from Frankfurt who at the beginning of the 20th century had moved to England, became naturalised as a British subject and then went to Argentina to source quebracho wood for the Argentine Great Southern Railways and to serve as a director of the Western Telegraph Company. In 1918 he acquired the rights to vast tracts of land in Misiones, a frontier territory that the national government was keen to populate. I shall return to Schwelm – a controversial figure – in future blog posts which will focus on Colonia Victoria, the last of the many failed attempts to create British agricultural “colonies” in South America.

Schwelm’s first Misiones venture was Eldorado, founded in 1919. Eldorado initially mainly attracted Danes, but there were soon were followed by Swiss, Germans (from various parts of Europe as well as from southern Brazil) and a sprinkling of people of other nationalities. Unlike the rest of Argentina, where individual landholdings tend to be in the hundreds – or even thousands – of hectares, properties in Eldorado (as in much of the rest of Misiones) were relatively small, generally measuring just a few dozen hectares, the aim being to create a class of independent family farmers.

From my base in Eldorado, Michael Nottidge and Daphne Cooper de Colcombet – both of whom as children lived in Colonia Victoria – introduced me to elderly local residents who had arrived from Europe in the 1920s or 1930s and who had memories of the British presence. I recorded some of the conversations and when I recently listened to the tapes, it occurred to me that apart from a dwindling number of local residents who arrived in Argentina as young children, the immigrant generation has by now entirely disappeared. This post records the recollections of just one of the individuals I met, but the memories of others will feature in future posts that deal with the curious story of Colonia Victoria.

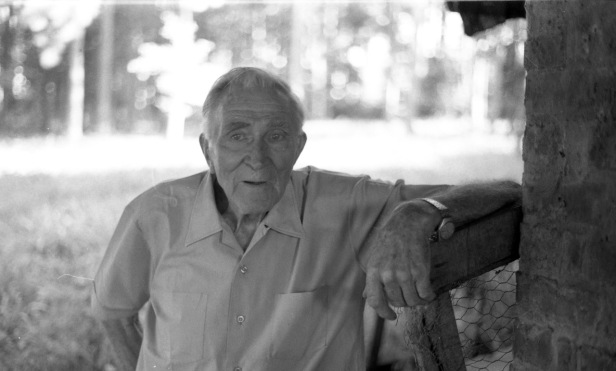

Carlos Strehler (born Trieste, 1899)

Everyone to whom I was introduced had a unique story explaining how they had ended up in Misiones, a place that in the early part of the 20th century was a remote, forest-covered, sub-tropical corner of Argentina. The journey alone was long and sometimes difficult: by ship across the Atlantic to Argentina’s thriving capital city, Buenos Aires; by train (or sometimes boat) to Posadas, the capital of Misiones; and by boat up river along the Alto Paraná – the Upper Paraná – to either Puerto Eldorado or Puerto Victoria. Of the immigrants who made their way to Misiones, a large proportion soon left for Buenos Aires or returned to Europe, unable to manage the vigours and isolation of pioneer life or to support themselves until their first harvests. But many stayed put and today Eldorado is the third largest centre of population in Misiones.

One of the people who I met was Carlos Strehler, a fairly early arrival in Eldorado. Don Carlos was born in Trieste, a cosmopolitan city, as was typical of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with Italians, Slovenes, Jews and Austrians being the main ethnicities. Trieste was Austria’s main trading port, an outlet to Adriatic Sea for Vienna, the Imperial capital. Trieste was – indeed, is – one of the main European coffee ports and by 1900 the city boasted many dozens of coffee trading and roasting companies. With its Viennese-style architecture and coffeehouses, Trieste was often said to be the only enclave of Mitteleuropa – Central Europe – south of the Alps.

With the breakup of the Austria-Hungary in 1918, Trieste’s fortunes were transformed. No longer was the city pivotal to the commerce of an empire, but instead its economy declined and then stagnated, becoming merely a provincial port on the extreme northeastern periphery of Italy. In the face of this, many people sought opportunities elsewhere. Argentina was a logical destination – one of the wealthiest countries in the Americas and far from the recent conflict that had shaken much of Europe. It was also well known to the people of Trieste as for decades Italy had been one Argentina’s main sources of immigrants, while Slovenes (from Austria, Italy and now the new Yugoslavia) were also moving there in significant numbers. It is little wonder that young, ambitious, Carlos Strehler would also look abroad for future – and be attracted by what Argentina appeared to offer.

One afternoon I was taken by Michael Nottidge to meet Carlos Strehler, who lived on his original landholding, a few kilometres from the town of Eldorado. Don Carlos was a few months short of ninety years of age, was still managing his property and was completely alert, darting from topic to topic, talking about the distant past and the present. Looking back I wish that my questions hadn’t been so focussed on Colonia Victoria, that I’d asked more about Don Carlos’ background and experiences. Even so, as he waited for the 5pm arrival of his day labourers to be paid, he told me something of how he came to Argentina and his life in Misiones….

“Strehler is really a Swiss name. If you go to Zurich, you have a whole town full of Strehlers! It’s the only place, because in Vienna there was only my family. But I was from Trieste.

I had the right to be an Italian after World War I. Trieste was almost a new Italian colony! In the first few years after the war, Austria was in a very bad economic situation, but in Italy things were far better. As we had our place and our business all in Trieste, if we chose to be Austrians, we thought, maybe they would take all this away from us. So we had to be Italian – and it was our right. They couldn’t say go away – go to Austria – because we were born in Trieste.

I worked with my brother selling tea for an English firm – that’s how I speak English. We sold to the Balkan countries because those people are tea drinkers. At that time you had there five or six kingdoms – Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Greece and all these countries – and we made quite a lot of money selling there. But after five or six years travelling, I had the impression that the communists are advancing. I told my brother – I was working with a brother of mine – let’s sell everything and let’s go somewhere very far from communism. Then some people told me that in Argentina they are planting a green tea that’s quite promising. It’s just started and everyday the people are drinking more of this ‘yerba mate’.

I came first to see if it’s true. I came to Buenos Aires, didn’t ask anybody nothing, but just went to the Alto Paraná. I came to Eldorado, made some exploration and I had a good impression. I thought, okay, let’s come to this place. I went to the company, to the land sellers. That was on 19 May 1926. He sold me 375 hectares of land. It was rather cheap at that time. [At this point, Michael Nottidge commented: “He was the biggest – by a long shot!”]

It’s not easy to start a colony and Schwelm had many problems because most people who came here without any money – they were very poor people, no? And he always had problems to get enough fresh money from Buenos Aires to keep the thing going. But he was indeed a very intelligent man. He was a German Jew. He changed his nationality to English. He always said “I’m English. I’m English!”

For people who came here without any money it was very hard, very hard. Yes indeed! They thought that Schwelm was the man who was culpable – umm – guilty. And in a way, yes, but in every other part of Misiones it was the same thing. You had many colonies, many places where people started to work. But it was not easy. No, it was not easy and now it is more difficult. I wouldn’t start now! Now it’s quite difficult. Argentina has gone down. Peron ruined the country. Peron ruined it with his stupid ideas.

I had people working for me. They came from Paraguay – half Indians. Many hundreds. We had a lot of them. The heavy work we couldn’t do – we didn’t do – because those people were much more capable than we. And it wasn’t so expensive, you know? To clear forest it was rather cheap.

I’ll tell you, twenty to thirty percent of the people who came to Eldorado had some money. They had enough money to start. Not very rich people, of course not. The very poor people they could get some work, some income, from the richer people who brought here some capital. It was a nice combination. Here in Eldorado, the ninety percent of the people came from places where they were no better off than here. From Poland, from the southern part of Russia. They were very modest, they were not accustomed to a better life. They worked without complaint.

I and my brother owned one of the first drying plants. First we planted the yerba and when we had the trees, we started to dry the leaves. They used here a very primitive system in the first years, but we modernised this completely. It was handwork but we started to mechanize in many ways. It was the same system which you dry tea with a belt. A moving belt. I have a national patente here, in Argentina. I developed it.

I worked like hell. But I couldn’t see how the poor people working drying yerba in that terrible heat. After two or three years they were terribly sick – their heart and lungs. And so I thought, no, no, we have to reform this and I started to mechanise and this cost me a lot of work and enough money because it wasn’t easy. Because if you have only a certain quantity of money and here there was no bank, nobody it going to help you. Well, you had to do it with your brain, with your money that wasn’t much and with your hands. Yes, for a few years we had to work like that. But I could mechanise so that where there were twenty people working, now there are two or three. And a far bigger quantity of yerba.

Citrus is not good for Misiones. It’s a mistake. I know. For a few years you have a nice crop. The plant should live for forty or fifty years, but here it’s only fifteen or twelve. You see, I have ten hectares of lemon trees, not older than fifteen or sixteen years. I had four or five good years of crops but now the half of the trees don’t give any fruit. The quantity is not enough to harvest – it’s too expensive. After so many years we know what’s good for Misiones: it’s yerba mate and forestation. If you make it good, a fine forestation of pine trees, that gives – slowly – some solid basis. And yerba maté always gave some profit and it’s a long-living plant – fifty, sixty years. It’s the people’s drink – everybody drinks it. It’s not for wealthy people only. I did for many years yerba mate planting, elaboration and roasting. That was my work. I made some money – but I’m easy in spending!

….Well, the English people thought it was as in the old times in their own colonies. The English mentality is different. They didn’t come here to work heavily. I know! They had some money and made some plantation, pero – but – mostly they were sitting below a great tree, in the shade, have a nice drink, stayed in nice a hotel for two or three years or as far as the money lasted. They had a nice life. But when they finished their money, they went away, sold their plantations. Those plantations were new ones, which they had to sell cheap. They sold to many people in Eldorado. I remember. Most of them went away.

The Mackenzies were my special friends. The old man, he was a chemical engineer. He was retired. He had an income, a pension, from his company, but he sold it, he converted it to invest in Victoria. He started with a very nice house but it was too expensive for him. Well, when he started with a plantation there was no money left. He spent all his money on his house! A wonderful house – a special house. There were two sons there, I remember. Then there was Hawkins who had a shop. But there were also many others.

And, no, it wasn’t the whiskey why the English couldn’t make it there. Everyone drank a bit when they were young. No, it was the mentality – the whole mentality of most of those people. They shouldn’t have brought them to this place – to Misiones – because the English people, fifty years ago, the whole world, they thought was theirs. But things were changing….”

If you want to be notified of future posts of The World Elsewhere (possibly including ones about Colonia Victoria!), please visit the homepage to subscribe to the blog and/or “like” the Facebook page!

I’m making my way to Misiones – via Uruguay – as I read this fascinating piece 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes indeed – there’s much more to Misiones than just Iguazú!!

LikeLike

So you’re actually on your way to Misiones now?? Where are going?

LikeLike

I’m just going for the more obvious reason – the falls. It’s a bit of a whistle-stop trip this: BA-colonia-Montevideo-BA-iguaza-el calafate-Puerto Natales-el calafate-BA over three weeks

LikeLike

Well, the falls are impressive! And I rather like Puerto Iguazú – it still has something of a frontier feel to it. Foz do Iguaçu, however, is pretty awful! I look forward to reading your blog posts that result from this trip….

LikeLike

I too arrived in Eldorado in 1989. I stayed for a few years, starting a family. I also became friends with Miguel Nottidge–who introduced me to his inner circle of friends. We would go bowling (Argentina style), have a little wine, and tell great stories. Great fun. My daughter left there recently and is now living in Miami with a girl friend of hers, who is also from Eldorado. And I am still good friends with Miguel’s son Francis Nottidge, who was nice enough to share this article with me. it brings back great memories, of a place lost in time….

LikeLiked by 1 person

How very interesting! Eldorado is a very particular place!…

Of course it was Miguel – Michael – who introduced me to Carlos Strehler. My main reason for going to Misiones was to visit Colonia Victoria and to meet the last people with direct experience of that very strange British agricultural settlement. I’ll be producing a series of blog posts on this.

LikeLike

Hi Oliver

I was born in Eldorado in the sixties but left at age 3 for England. My grandparents were the Lambert family who went to Victoria in the 1930s. I would love to hear more of your stories from the people of the past

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Liz, It was great that you found this blogpost and thank you for leaving a comment. I’ll send you an email – my intention is to write much more on Colonia Victoria, where your grandparents settled.

LikeLike

Hi Oliver!

I am Carlos Strehler’s grandchild.

In the last years of his life, my grandfather always talked about this English journalist that came over his place searching for information about the ”Eldorado’s Pioneers’’.

We always wandered whom this person was and if it really existed…

And here you are.

It’s amazing to find this blog!!!!

You have done an excellent job!

Thank you!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Miguel, I’m really pleased that you found this blog post about your grandfather. It is wonderful to receive a comments or messages from family members of people who I’ve written about – and I’m always relieved when I’m told that I’ve successfully captured something about their relatives. I have a few questions for you about Carlos Strehler – I’ll send you an email.

LikeLike