In southern Indiana, in the American Midwest, there’s town called Brazil. Throughout North America, settlements were often named after a place, almost always in Europe, to which the founders had links. When planning a road trip this summer, I noticed a “Brazil” on the map just north of the portion of the Interstate Highway I-70 on my route. Naturally I was intrigued.

Not for a moment did I believe that this particular Brazil had been established by South American immigrants, in the way that Germans, English, Scottish, French and other settlers had founded other Midwestern communities. Instead I suspected that the name came about in one of two possible ways.

Immediately after the Civil War, thousands of defeated Confederates left their devastated homeland for self-exile in Latin America. Most were attracted by farming opportunities in Brazil, one of the last slave-holding societies in the Americas. While some of these migrants remained – and even prospered – in Brazil, many returned to the United States, either to their former home states or to elsewhere in the country. I was aware that in Tennessee there’s a village that in 1869 was named to commemorate the emigration to Brazil, so it was possible that a returnee from South America had moved to Indiana and named a settlement after the country to which he had sought refuge.

More likely, I thought, the town was founded by a pioneer with the not altogether uncommon Irish surname of “Brazil”. This seemed like a strong possibility given that in the 19th century there was a relatively small but steady inflow of immigrants from Ireland in Indiana, as well many more people of Irish origin arriving from other states. There are countless places – large and small – in Indiana named after families, so why couldn’t one of these have been named Brazil?

It didn’t take long to realise that neither of these assumptions was correct. Instead, the reality is more mundane. Rather than the town having born witness to a historic event or individual, the name “Brazil” was selected almost entirely randomly.

Oral tradition (as detailed in The Brazil Times of 26 April 1926) has it that the town of Brazil got its name from William “Yankee Bill” Stewart (1817–95), a carpenter and millwright originally from Massachusetts. As a child he had moved to New York, and from there his family went to Ohio and finally, in the 1830s, settled in Indiana, a common migration pattern in the early decades of the 19th century.

One day in 1844, Yankee Bill was sitting with Owen Thorpe, a local landowner, discussing the possibility of creating a settlement along the National Road (the future U.S. Route 40) that passed through the area. Thorpe sought a suitable name for his proposed new town and asked his friend, who was known for being a careful reader of newspapers that sometimes made their way into this backwoods territory, for ideas. Sometime before, Yankee Bill had been reading about a “revolution” in far-off Brazil, and he suggested that as the name of a future town, the word being short and easy to remember.*

(It is unclear as to what “revolution” Yankee Bill’s attention was drawn. In the 1830s and early 1840s a number of significant rebellions in Brazil, South America had, however, made international news, with the Guerra dos Farroupilha – the Ragamuffin War – attracting particular attention. Involving the Italian revolutionary Giuseppie Garibaldi, this republican uprising took place between 1835 and 1845 and included demands for secession of the southern provinces of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina.)

In its early years, Brazil served as little more than a stopping-off point for wagon trains carrying people to new lives further West. Prospects for the community changed in the 1850s when coal and pottery clay deposits were discovered locally. For a time coal mining was a significant activity, but it was more as a clay and brick producer that Brazil came to flourish. At its peak, there were nine clay plants within a couple of miles of the town, producing electrical conduits, tiles, blocks and bricks of all varieties, sewer pipes, chimney flues and tops and other items.

As this industry grew, so too did Brazil’s population. By 1873 the town had more than 2,000 inhabitants, reaching 9,300 in 1910 and supporting an extensive range of stores, hotels, banks, schools, medical facilities and theatres. By 1960 the population had dipped slightly to just under 9,000, a figure that has remained fairly stable, despite the complete closure of clay-related industries.

For its first hundred years, the town of Brazil and its South American namesake didn’t have even the faintest of connections. This changed as a consequence of an 11-day visit, in May 1949, to the USA by the Brazilian president, Eurico Gaspar Dutra. The USA and Brazil had already developed a close, yet sometimes difficult, relationship, but ties improved during World War II when Dutra served as Minister of War. Despite being ruled by an authoritarian president, Getúlio Vargas, with fascist sympathies, Brazil joined the war alongside the Allied powers; US airforce bases were established in the Northeast of Brazil, and US and Brazilian military units fought alongside each other in the Italian campaign.

In 1946 Dutra was elected president, strengthening economic and political ties between the USA and Brazil at what was the beginning the Cold War era. Noted for his very pro-American positions, outlawing the Communist Party and breaking off relations with the USSR, Dutra was invited to visit the USA. Apart from a few days in Washington, D.C. (where Dutra addressed Congress) and in New York City (where he inspected the construction site of the United Nations Headquarters), the president spent most of his time in Tennessee. There he participated in a programme that included meeting with officials of the Tennessee Valley Authority (a prominent regional development initiative), opening Vanderbilt University’s Institute of Brazilian Studies and visiting the village of Brazil.

Plans for Dutra’s Tennessee visit had caught the attention of Don Bolt, a popular commentator and lecturer on Latin American affairs and a native of Brazil, Indiana. The Brazilian president was sent an invitation to visit “the clay products center of the world”, but whether due to pressure of time or lack of interest, nothing came of it. Nevertheless, contact between the two Brazils was pursued, and soon Brazil’s ambassador to the USA, Maurício Nabuco, visited the Indiana town. It was from these contacts that the idea emerged for the Brazilian government to offer Brazil, Indiana, a monument as an expression of Brazilian-American friendship and common interests.

In 1950 the Brazilian sculptor Tito Bernucci was selected to produce a replica of the Chafariz dos Contos, or the Fountain of the Tales, the mid-18th century original of which is located in Ouro Preto, a colonial-era gold mining town in Minas Gerais that since 1937 had been protected as a Brazilian national monument.

Built of plastered sandstone, the Baroque-style Chafariz dos Contos was created to provide water for humans, mules and horses. Why it was decided to produce a copy particular monument is, like so much connected to this story, unclear. Perhaps someone imagined that the two were vaguely connected with respect to their mining histories – or perhaps, like the naming process for the town century before, it was an appropriately random decision.

For his fountain, Bernucci used brick and sculptured granite, reproducing the twists and turns of two large and wide-hewed volutes, the central space that incorporated a large shell supported in a carved bowl. The completed structure weighed 62 tons (some 56,000 kilograms), measured 26 feet (8 metres) high and 40 feet (12 metres) long and bore the inscription “From the Republic of Brazil, a token of friendship to her namesake the city of Brazil, 1954.”

In December 1953, Homar E. Capehart, US senator for Indiana, visited Brazil while on a two-month study tour of Latin America as chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency. While in Rio de Janeiro he attended a ceremony, presided over by President Getúlio Vargas (who previously had governed as a dictator, but was now Dutra’s elected successor) to accept the monument.

The following April, George H. James, the editor of the The Brazil Times, also visited the Brazilian capital, delivering President Vargas an invitation from the mayor of Brazil and the governor of Indiana to attend the fountain’s inauguration. Vargas expressed polite interest and promised to send a representative. Under Vargas, however, relations between Brazil and the USA grew increasingly strained, while his government became mired in political and economic difficulties. As pressure from the army mounted for Vargas to resign, the politically isolated president spiralled into a state of deep depression, and in the early hours of 24 August 1954 he committed suicide, shooting himself through his heart.

Over the following 18 months, a succession of four different presidents were sworn into office. Hardly surprisingly, the least of the concerns for the authorities in Rio de Janeiro was a gift for a small town in the US Midwest. Not until 1955 were the 104 crates containing the monument dispatched, sent by ship to Baltimore and then transported onwards by rail to Indiana. After delays that had stretched into years, the new Chafariz dos Contos reached its permanent home, where it was erected at the entrance to Forest Park, Brazil’s main recreational ground, located alongside State Road 59, on the south side of town.

Now that the monument was finally in situ, what was needed was a suitably grand unveiling: the civic authorities believed that a celebration, the likes of which had never been staged in the Midwest, would put Brazil – that is, Brazil, Indiana – on the state, national and international maps. Celebrations were planned to take place in the afternoon and evening of Saturday, 26 May 1956, and plans to cover the event in detail were made by staff of the The Brazil Times for the federal government’s United States Information Agency (which, in turn, would supply reports to Brazilian newspapers) as well as by reporters and photographers coming from Indianapolis, Chicago and other metropolitan centres.

A parade – something that small towns in both America and Brazil do so well – was to be a central public element of what would surely be the first ever Brazilian-American festa to be staged in the Midwest. A theme of “Ordem e Progresso” (Order and Progress), Brazil’s national motto, was decided on, and for the big day the town was emblazoned with blue, green and yellow Brazilian flags, alongside red, white and blue banners of the USA. The parade, featuring floats sponsored by local clubs and businesses and civic and high school marching bands, was expected to take an hour to make its way from downtown Brazil to Forest Park. Meanwhile “jet planes” of the Indiana National Guard were set to stage a fly-past, and a plane chartered by the Brazilian Coffee Institute was to drop bags of coffee. Some 20,000 spectators were expected to line the route and gather for the unveiling of the Chafariz dos Contos, while thousands of free cups of coffee (“brewed by experts”) and Brazil nut cookies were to be served – this being the 1950s – by members of the town’s Business and Professional Women’s Club.

Despite the careful planning, not all was in the control of the organising committee. After several days of beautiful weather, before daybreak on the Saturday torrential rain began falling, and it continued raining intermittently throughout the day. The organisers were despondent as they cancelled the parade and the celebrations at the park and grounded the planes.

After initially paring back the events to just a banquet for local and visiting dignitaries at the Elks Club, an important meeting place for local business and civic leaders, it was decided that this would be unfair to the public. Instead, coffee was served “under the difficulties of heavy rain” to people who insisted on gathering both downtown and at the monument, but the ceremony was transferred to Brazil’s largest auditorium. There, lights and a public address system, strong enough to drown out the patter of rain on the roof, were hastily installed.

The musicians who were to parade through town had all been sent home, but a new band was speedily assembled at the auditorium. They naturally had no problem performing the American national anthem, but with barely any rehearsal time – and to the surprise of many – they “masterly” handled the “long and difficult” Brazilian anthem.

The guest of honour representing Brazil, South America, was João Carlos Muniz, the Brazilian ambassador in Washington, D.C. He was accompanied by seven embassy colleagues and – to the evident delight of a reporter from The Brazil Times – by the ambassador’s “beautiful daughter”, the Marquesa de Belmonte. The diplomatic party was joined by Brazilian students studying at various universities in Indiana and elsewhere in the Midwest.

As the rain pounded on the roof of the auditorium, Muniz delivered a speech praising the people of Brazil, Indiana, for his reception and paid particular tribute to two of his fellow guests who he said had done much to promote goodwill between the countries – Senator Capehart and to Don Bolt, “that live wire from Brazil, Indiana”.

In the name of the Government and the people of Brazil, from whom I bring you a cordial message and greetings, I have the honor to salute the city of Brazil on this occasion of the dedication of the monument presented by my country as a token of friendship and symbol of the ties of mutual understanding which bind our two nations together. By a fortunate coincidence, the inauguration of the Chafariz dos Contos occurs on a date which is significant to the relations between our two countries, for it was exactly 132 years ago, on May 26, 1824, that the first diplomatic representative of the then Empire of Brazil was received officially in Washington, following the political recognition by President Monroe’s government of the independence of Brazil. (João Carlos Muniz)

Although Muniz spoke at length about Brazilian history (and, specifically, the history of Ouro Preto, the colonial-era city “of which the Brazilian people are justly proud”), he was keen to emphasise the achievements of modern Brazil, specifically the steel mill of Volta Redonda, near Rio de Janeiro,”a monument to the future, marking the beginning of the economic independence of the country, which will also be a source of pride to generations still unborn”.

This being a major event for such a small town, local and state dignitaries from the worlds of politics, education, business and religion were out in force. Mayor Ted McCoy, on behalf of the city, accepted the monument, while Governor George N. Craig spoke on behalf of the state.

We proudly accept the gift from the republic of Brazil in South America. You will never meet people who are more humble than you will find here, nor more fervent for peace and good will. Neither will you find people more vicious for furtherance of this freedom. We are happy to receive this splendid token and may the sun never set on the friendships of these two great peoples. (George N. Craig)

Senator Homer E. Capehart, who had visited Latin America and regarded himself as something of an expert regarding Brazil, said that he considered the future development of South America as being of vital interest to the people of North America, offering the potential of hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

I say to you that none can tell how important to the future of both nations is the presence here today of the Brazilian Ambassador to the United States, representing the President of his great nation. The citizens of the city of Brazil, Indiana, are to be congratulated upon the magnificent job they have done in arranging this wonderful event. As their United States senator, I pledge to them and to the President, the Ambassador and the people of the nation of Brazil my continued 100 per cent cooperation in furthering the fine relationship that is vital to the future of both of our countries. (Homer E. Capehart)

Telegrams from President Dweight Eisenhower, Vice-President Richard Nixon and from Vice-President João Goulart of Brazil were read out, all expressing interest in the event and extending greetings. Local church leaders offered prayers. Following the speeches and readings, hundreds of people lingered to drink coffee being distributed by the busy members of the Business and Professional Women’s Club who had been redeployed to the auditorium.

In the years immediately following the monument’s inauguration, Brazil continued to receive a small but steady flow of Brazilian visitors, playing on the town’s distinctive name and links with the Brazilian Embassy in Washington, D.C. For example, a group of Brazilian home economics teachers under the US government’s Agency for International Development was directed to this rather ordinary Midwestern small town, as was a group of Brazilian bankers studying farm credit nearby at the Purdue University, while curious Brazilian students studying at Indiana University, just 50 miles to the southeast, occasionally stopped by. The Brazil Times was always keen to highlight such visits, to the extent of offering as a headline, on 2 May 1959, “Lone Brazilian spends the night here” after receiving a tip-off that an individual had booked into a local motel. No more gifts arrived from South America, though in 1969 the Brazilian Embassy sent the town, for no apparent reason, a Christmas tree.

Strangely, perhaps, local entrepreneurs rarely played on a newfound connection between the town of Brazil and the more exotic Brazil to the south. In the late 1950s visitors to town were welcomed by a large billboard boasting of the Chafariz dos Contos and adorned with an image of a vaguely Carmen Miranda-like figure balancing a bowl of tropical fruit on her head. There was also the Brazilian Bowling Lanes, opened in 1962, which had as a feature an illuminated palm tree, suggesting the Brazil to the distant south.

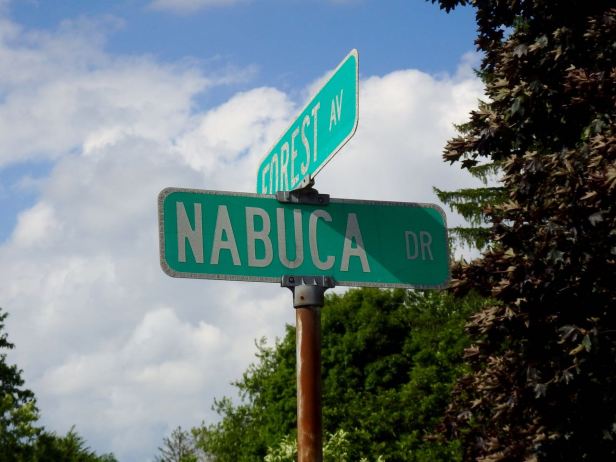

For a while there was discussion of opening a Brazilian-themed souvenir flower garden, store and café alongside the Chafariz dos Contos itself, but nothing came of the idea. (Instead, located alongside the monument, there is road named in honour of Maurício Nabuco, the Brazilian ambassador under whom ties between the two Brazils first developed. But even this small gesture is mistaken: on the street sign and on Google maps the ambassador’s name is mis-spelled, reading “Nabuca Drive“.)

While Brazil is an attractive enough town, with some handsome late 19th and early 20th centuries buildings constructed from local bricks and pleasant suburban homes with neatly trimmed lawns, it is hardly likely to attract people seeking a Brazilian experience. Still, with a little imagination, a visiting Brazilian might find something vaguely familiar on the menu of the rather good barbecue restaurant in downtown Brazil – though here, in southern Indiana, barbecue is represented by pulled-pork, smoked chicken and meatloaf, not the grilled meats of a typical Brazilian churrascaria. Perhaps the menu could be just slightly tweaked?

The connections that briefly were brought about linking Brazil, Indiana with Brazil, South America, faded quickly. Today there’s certainly no Brazilian presence in the town. It would have been nice to have discovered a “Brazilian-Brazilian” community, but there doesn’t seem to be a single actual Brazilian living in Brazil, Indiana. All that exists of South America in this far flung Brazil is the replica of Ouro Preto’s Chafariz dos Contos that was brought to Indiana at considerable diplomatic and logistical effort. Standing alongside what was intended as a permanent symbol of Brazilian-American friendship, is a single flagpole, flying the Stars and Stripes. The lack of a flagpole flying a Brazilian flag, combined with the fact that the fountain no longer functions, only emphasises that the town’s name, like its transplanted Chafariz dos Contos, lacks like any real meaning.

Well, thank you Oliver Marshall! I enjoyed the twists & turns of this strange tale very much! Beautiful “slide show” and well-told.

(By the way, my home state, New York, has a Mexico, Cuba, Peru,etc. but somehow, no Brazil. Or an Oliver, for that matter. But it does have both an “Olive” and a “Marshall”)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Robert! I’ve sometimes thought about looking at places around the world called “Bristol” (my place of birth in England). I’ve been to Bristol, Vermont – I’m guessing that there’s also a Bristol, New York. By the way, I’ve enjoyed your recent photo-based blog posts of your home area…but I hope that you also get to do some more travelling soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely, I learned to ski in Bristol,NY!

I’ve been posting photos of home, but I’m currently in Chile, teaching English. In a few weeks I’ll be done and will travel around a bit before I head home. It is a beautiful country

You would be interested in the German influences in this region, although there’s only a few vestiges in this town, Pucon, and haven’t had much opportunity to talk to any older residents. I probably won’t post any pictures from Chile until I’m back in the US

LikeLike

Robert: I for one certainly look forward to any future Chilean posts of yours!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool. Vienna, Virginia, where I live, is named after Vienna, New York, which may be named after the city in Austria. I’ve never bothered to find out. In fact, when people ask me how to spell “Vienna,” I usually answer “like the city in Austria.” This being the United States, I then get a blank stare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Or you could confuse people even further by spelling it “Wien” – using the “correct”(German) name!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting article about a curious diplomatic story involving two completely different huge countries and two lovely towns: Brazil, Indiana, and Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais.

Loved it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Graça. True, the US and Brazil are both huge – and they have a surprising amount in common. As for Brazil, Indiana and Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais….all that I can say is that I doubt that the former will be granted by UNESCO World Heritage status any time soon!

LikeLike

The band that played the Brazilian anthem that day is the Jackson Township Community Band which still exists, and still has the music. A grant has been received to study the renovation of the fountain which in my lifetime never really worked very well. Donations may be sent to Clay Community Parks Association, Inc. http://www.insideindianabusiness.com/story/32231894/study-to-focus-on-brazilian-fountain

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment. I guess that there must be some (now elderly) people still around who have memories of the celebrations of 60 years ago. It’s good that efforts are being made to restore the fountain. Maybe a grant will also be sought to pay for a second flag pole from which the Brazilian flag will fly!

LikeLike

I considered your article rude and degrading. I grew up in Brazil, Indiana and had a safe and happy childhood. It seems to me your article, and I use that term loosely, paints a picture of a small town not worthy of existence. Perhaps you should return to merry ole England and bash a few towns there.

LikeLike

I’m sorry that you regarded this blogpost in such a negative way. I really cannot see how the post might suggest that I feel that Brazil, Indiana, is somehow not worthy of existence. The post simply relates to the distinctive name of Brazil, Indiana and to a small episode in diplomatic history involving a place that briefly became a symbol of friendship between two important countries. It’s true that places sometimes owe their names to random decisions and this is strikingly the case for Brazil, Indiana. As far as the naming process is concerned of what would eventually be your hometown, there was not even the remotest connection with the country that inspired the name. Such a lack of a connection remained true for most of the town’s existence. Despite this, I felt that it was rather interesting how, for a relatively short period of time, your small Midwestern town forged links with South America’s largest country.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also grew up in Brazil, IN. The author did an amazing job playing-up the intricacies of Brazil, IN and making an otherwise quiet, aimless, and depressive town look remotely interesting. Ask any Brazil-billy and they’ll tell you: there’s not much to do in Brazil. We used to have a skating rink a long time ago but that’s long gone. Then there’s the rotation of gaming stores that kept going out of business, the ones that had the rampant drug problems with the high-school drop outs in the back. Bravo to the author for making this dusty old town look lively and showing off its better traits.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Tyler, for your interesting – and dryly amusing! – insights into Brazil, Indiana. I’ve only visited your Brazil twice and what attracted me was simply to investigate the story of the town’s name. But based on my admittedly short visits, it’s obvious that Brazil has seen better days. That’s not to say that its imposing public buildings and rather charming-looking main street aren’t well-cared for, but simply that the economic basis of the town has largely collapsed. Hopefully Brazil finds a way forward, but it may suffer being located just on the doorstep of Terre Haute, a much more economically and culturally dynamic town.

LikeLike

Just like the article, you rattled on and on while saying nothing! You are correct when you state it relates to a ‘small episode,’ while most of the population of the town and surrounding area were more concerned with daily life than the name of the town. You obviously do not understand rural America. Like a lot of rural towns in America during the fifties era, what made the town thrive basically ‘ran dry.’ The ‘not worthy of existence’ comment stems from all the negative comments made in the article, ‘the fountain doesn’t work, there should be another flag pole, barbecue is different, etc.’ So speaking as a person who grew up in ‘ a rather ordinary small Midwest town’ (your words) and my opinion only, you should concentrate on writing articles about places where you have actually lived and can relate to.

LikeLike

That’s so interesting! I am a Brazilian and always wondered about the history of Brazil, IN. Thanks for sharing; it was really interesting. Now, whoever is born in Brazil, IN, is a “Brazilian”? I wonder if this puzzles people when they ask and see a very white “Brazilian”? Lol

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, João, for your comment – it’s nice to hear that I wasn’t the only person curious about Brazil, IN. Apparently the inhabitants refer to themselves (and are referred to by as others) as “residents of Brazil” or “inhabitants of Brazil” – and only rarely as “Brazilians”. That’s a pity t as given the fact that the Brazilian (SA!) diaspora is huge in the States (including, certainly, in Indianapolis and some of Indiana’s college towns), there would then have been the possibility of the existence of the odd “Brazilian-Brazilian”! (I am not, as the previous commentator seems to believe, making fun of the town – it’s simply that it’s rather fun that there’s a Brazil in Indiana!) Where, by the way, do you live: in the US or in Brazil, SA?

LikeLike

Meu nome é Lucas e foi bem legal conhecer a história dessa cidade…e bom é engraçado saber que existe cidades em outros países com o nome do seu país e dado em homenagem a ele..

LikeLiked by 1 person

I grew up in Brazil IN and was 12 when the Chafariz dos Contos fountain was dedicated in Forest Park. It was a big deal for the city. Like Virginia Meek, the tone in Marshall’s story is offensive to me. Even his apology is offensive. Why waste a good collection of information about Brazil by insulting current and former residents? (e.g., the title of the story.) Marshall’s tone reminds me of a song written by Alan Barcus, my high school track coach who lived in Brazil during the 60’s. It’s title is The Critic’s Lullaby, and if you have Spotify, you can hear it at https://open.spotify.com/track/28ECTJS6kLgIgVnLSq7Ir3?si=yT4GVFyuSbODRKV8JW-0ZA. By the way, a $50,000 project is underway to give the fountain a facelift. But the project doesn’t include a second flagpole for the Brazilian SA flag. I’ve offered to chip in some money for this flagpole. Hey Marshall, want to help out?

LikeLike

Hi Marshall, nice story.

Greetings from a Brazilian.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Paulo! (Am I right to assume that you’re a Brazilian from Brazil, South America and not a “Brazilian” from

Indiana?)

LikeLike

Amazing history Marshall, congratulations! I am brazilian, and I have always been interested in knowing the history of the city with the same name as my country. Here in Brazil, some television reports were made, but only visiting the city and showing the existence, but without much information about its history. It is sad that there is no presence of Brazilian immigrants in the city, it would certainly be a source of pride for many of us to have a place with the name of our country and with our characteristics!

LikeLiked by 1 person