It was almost by accident that I came across the old Sephardic Jewish Cemetery of Lisbon’s Estrela neighbourhood. When I mentioned to a friend that I would be visiting the city’s British Cemetery, he told me that he had heard that somewhere nearby there was also a Jewish one.

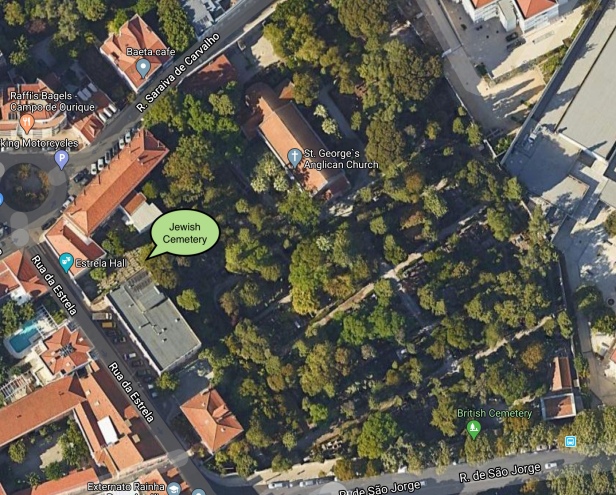

While walking, the following morning, through the tree-shaded grounds of the British Cemetery, I was fortunate in meeting Andrew Swinnerton, its administrator. He explained that the Jewish Cemetery directly adjoins the British Cemetery and pointed me towards a path leading to a high wall that separates the two burial grounds.

* * *

In 1497, King Manoel I of Portugal issued an edict demanding that Jews either convert to Christianity or leave the country. In the following years and decades, tens of thousands of Jews fled Portugal, including many of the so-called the “New Christians”, or “conversos“, whose lives were made intolerable, being subject to pogroms and the iron hand of the Holy Inquisition.

As a consequence of these expulsions, Sephardic Portuguese (and Spanish) Jewish communities were established across North Africa, southern Europe and further afield. Most of these exiles found new homes under the protection of the sultans and caliphs of the Ottoman Empire and of Morocco. Others fled north to Amsterdam, London, Hamburg and other trading centres, or across the Atlantic to Curaçao, New Amsterdam (Manhattan), Suriname, Pernambuco and elsewhere in the “New World”.

Some three hundred year after leaving Portugal, Jewish merchants started trickling back to their ancestral homeland. Although there were still strict restrictions placed on Jews in the country, as foreigners the new arrivals could count on at least some protection.

Thanks to the special relationship that existed between Britain and Portugal, Sephardim from London and especially Gibraltar (which since 1713 had been a British territory) became something of a significant presence in Lisbon. But well into the 19th century, Lisbon’s Jewish community was in a delicate position. Catholicism was the sole religion permitted to Portuguese citizens and as such the Jews had no legal existence and the community was regarded as being a foreign colony.

Soon after the return of Jews to Lisbon, with the pre-expulsion Jewish cemeteries having long-since been destroyed, it became clear that a burial ground would be needed. Because many members of this new community were British subjects, a corner of the Protestant British Cemetery (or the “English Burial Ground”, as it was called when created in 1721) was sectioned off for their use.

The Estrela Jewish cemetery’s first grave was that of José Amzalaga, who died on 26 February 1804. For some sixty years this was Lisbon’s only Jewish cemetery, the final resting place of British, Moroccan and other Sephardim, and increasingly their Portuguese-born co-religionists. The last burial took place in 1865 by which time no more space remained. A new Jewish cemetery was established in 1868, one that remains in use to this day.

* * *

Access to the Jewish Cemetery is restricted, its large metal doors almost always locked and at street level it is impossible to see over its high walls.

Approaching from the British Cemetery, however, I was able to open a flimsy cardboard door leading to the grounds of a vacant neighbouring building, the former British Hospital. This, along with the Anglican parsonage, the Royal British Club and the Estrela Hall (the longtime home of Lisbon Players, an English-language theatre company), was once part of Lisbon’s so-called “British Quarter”. After well over three hundred years of British Crown ownership, the British government sold these buildings in 2018 to a real estate developer. Whereas the British Cemetery and St George’s Anglican Church were not included in the sale, the Jewish Cemetery was – though fortunately this portion of the property will remain protected, under the care of Comunidade Israelita de Lisboa.

From the small rear courtyard of the former hospital, I was able climb a few steps onto a fire escape, lean over a high wall and peer into the compact grounds of this normally hidden cemetery. The one hundred and fifty or so tombstones, with inscriptions all seemingly in Hebrew, are laid horizontally, in traditional Sephardic fashion. Soon only the occupants of the planned luxury condominiums will have this privileged view. Hopefully they will appreciate it.

Date of photographs and video: Friday 14 February 2020.

Hello Oliver! You post infrequently, but always something worth reading. Even if it’s not made accessible to visitors, it’s good to see the burial ground looking well-maintained and not vandalized.

There’s a tiny Sephardic cemetery in Manhattan, I think in what’s now Chinatown, and I’m pretty sure the folks buried there, in the 17th c., were refugees from Portugal, arriving in New Amsterdam via the short-lived Dutch colony in Brazil.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s very kind of you, Robert. In reality you are a blogger to emulate: producing fairly frequent posts that are consistently interesting, both in words and photographs. As for the origins of the Jews (and Jewish cemetery) of colonial New Amsterdam, you’re absolutely right. I’ve never been to the Manhattan cemetery but will one day visit it. The colonial Jewish cemetery that I really want to see is further south: in Jodensavanne, Suriname!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Oliver for this interesting report .

Good to meet you this month , all best

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Andrew, for pointing me towards the Jewish cemetery. The timing of my visit was fortuitous. I’m hoping to produce a blogpost about the British Cemetery. Its story is rather more complex and I may first have to return to Lisbon. When I do, perhaps I can arrange to talk with you again.

LikeLike

On June 26, 1940 the main HIAS-HICEM (Jewish relief organization) European Office was authorized by Salazar to be transferred from Paris to Lisbon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, the developers have submitted a request to Lisbon’s municipal authorities asking for permission to cover the jewish cemitery with a canopy lest the future inhabitants of this quarter have their views disturbed by the tombs. No voices of Lisbon Israeli community condemning this request have been heard so far.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Incredible! Personally, I would love to live in an apartment that offers a view looking on to this very special cemetery.

LikeLike

So sad that the British Goverment ( ever knowing the ‘price of everything and the value of nothing ‘ ) sold those buildings for peanuts, when they held so much value, not only for the British community in Lisbon, but the wider community, being usable as public spaces for all.

From memory I believe I read that the UK Government also sold off its beautiful and prestigious Embassy building in the Lapa area : what kind of brain could think that a couple of million Euros was worth it in exchange for giving up all that history and prestige ? Difficult to imagine the Chinese or the Russians doing anything so utterly stupid.

LikeLiked by 1 person