Just over 100 kilometres north of the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre lies the old colonial zone of Rio Grande do Sul, the country’s southern-most state. At the start of the 19th century, the state was frontier territory, land that the newly independent Brazil was keen to protect from possible Argentine encroachment.

Rio Grande do Sul is covered by two main eco-regions: pampas grasslands in the south and hilly, even mountainous, territory in the north. The densely forest-covered mountains were entirely unsuited to the kind of plantation-based agriculture, worked by slave labour, that dominated tropical Brazil to the north. As such, in the early 19th century it was recognised that if this new land was to be exploited, an alternative settlement pattern was required.

Rio Grande do Sul was promoted by Brazilian immigration agents as being an ideal destination for land-hungry Europeans, in particularly for Germans and Italians, seeking to establish independent family farms. Germans first arrived in 1824, initially taking land to the immediate north of Porto Alegre. Most of these immigrants came from the mountains and valleys of the Rhineland-Palatinate region of the Hunsrück, its landscape remarkably similar to that of the Serra Gaúcha– the mountains of Rio Grande do Sul. This would remain an important destination until the late 1850s when most German states banned emigration to Brazil after news filtered back home of dreadful treatment of immigrant sharecroppers in the coffee-growing regions of São Paulo.

[Worth tracking down is Edgar Reitz’s 2013 film “Die Andere Heimat” – “Home from Home”. Set in the Hunsrück of the 1840s, a running theme of the film is the lure of Brazil, a place promoted to desperate would-be emigrants as a place of perpetual summer.]

Agents then turned their attention elsewhere in Europe and between 1875 and 1915 it was the hills and mountains of Veneto, in northeast Italy, that became the main sources of immigrants. These Venetians settled to the north of where the Germans had established themselves, taking land that was even more challenging to cultivate. Whereas Germans concentrated on mixed farming to supply the needs of Porto Alegre’s growing population, the Italians focussed on growing grapes and producing wine, using knowledge and skills that they had brought with them from Europe.

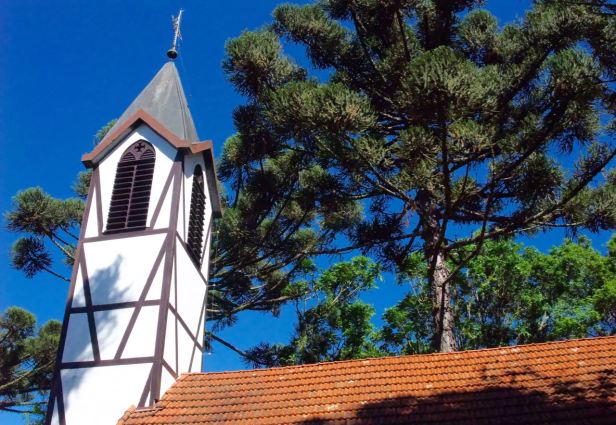

It is now almost two hundred years since the arrival of the first German immigrants in Rio Grande do Sul and just over one hundred years since the end of the wave of Italian immigration. Because the immigrants were concentrated in ethnically homogeneous groups, in what until quite recently have been relatively isolated areas, to this day German and Italian cultural traditions – including languages – remain strong, especially in the rural areas and villages.

“Riograndenser Hunsrückisch” gradually developed, a language based on the German immigrants’ Hunsrückisch dialect, elements of other German dialects and the inputs of Portuguese vocabulary and grammar. With the arrival of Italian immigrants, “Talian” slowly emerged as a dialect based on the Venetian language. During the course of the 20th century the linguistic presence of German and Italian appeared to be fading fast, but in recent decades the status of Riograndenser Hunsrückisch and Talian has improved with the languages receiving official recognition at a local level and even being taught in some public schools.

With a temperate climate of relatively cool winters and very warm summers, a European heritage and a picturesque landscape, many Brazilians view Rio Grande do Sul’s Serra Gaúcha as being an exotic contrast to the country’s imagined mainstream. Local tourist officials promote a folksy image, that of German-style bands pumping out merry “umpapa” tunes, enormous high teas (“café colonial“), Christmas markets and grape, wine and polenta festivals. Although this isn’t entirely a fabrication, realities are far more complex.

The rural inhabitants of the Serra Gaúcha have long faced similar problems to those experienced by smallholders elsewhere in Brazil, most notably fitting in with an agrarian system that has always favoured large producers. Here, some farmers have managed to integrate themselves with the agri-industrial complex by supplying grapes to large wine producers or contracted by corporations to produce chickens, pigs, milk or tobacco. While these ties may guarantee some security, the control of production is lost and sales to third parties (and possibly achieving higher prices) are not permitted.

[Grapes are the only commercial crop of many farms in the “Italian” areas of the Serra Gaúcha, where most Brazilian wine is produced. In the past most grapes were of the American Concord variety – which even do well with hot, damp summers – to produce wines that tastes much like an alcoholic version of Welch’s grape juice. Despite the planting of new grape varieties and huge efforts to develop more sophisticated wines, the local output is remains at best rather mediocre in quality, the main exceptions being sparkling wines, which can be excellent.]

As in many parts of modern western Europe, small-scale producers have had to find ways to supplement their farming incomes. Many take on part-time employment in factories or in agricultural processing plants. Some manage to involve themselves with tourism, perhaps producing jams and cakes, renting our rooms or dressing up to receive day visitors to their farms. Another survival strategy has been to sell up entirely and move to where land is much cheaper, including to the far-off Amazon.

Still, if you can see beyond the kitsch representation of the region’s German and Italian heritage, as well as past the very real contemporary struggles of the inhabitants, the Serra Gaúcha certainly has much to offer visitors. The landscape is dramatic, backroads lead to little-visited villages and farms where the inhabitants seem genuinely pleased to share with outsiders stories of their immigrant forebears and to talk about today’s way of life. And the cakes are usually excellent and, if you’re in the right mood, the wine is just about drinkable!

Very interesting article. I’ve seen mentions of German immigration to Chile after the 1848 revolutions, and I think there are some pockets of Mennonites, etc. in Mexico, but never read anything before about Brazil. My father’s family immigrated to Pennsylvania from the Palatinate — and I’m sure “Riograndenser Hunsrückisch” has a few words in common with “Pennsylvania Deitsch.” I’ll be going to Chile in a few months, don’t know what region yet, and will keep my eyes peeled/ears open for German influences there. Enjoyed the photos, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Google “Blumenau” and “Pomerode”. The german culture is very strong here in Southern Brazil.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment, Francisco! I’ve been several times to both Blumenau and Pomerode. Blumenau is a bit Disney-like, but Pomerode is a fascinating for how German culture managed to survive and evolve.

LikeLike

Thank you for your nice comment! Apart from in Rio Grande do Sul, the German language (or German dialects) and German culture (or variants) remains very much alive in various other parts of Brazil. I might sometime produce a blog post on Pomerode, in neighbouring Santa Catarina, a place that promotes itself as “the most German city in Brazil. (In reality it’s little more than a village but it is true that German is universally spoken both there and in the surrounding countryside.) I’ve also visited German communities in the state of Espirito Santo – the Brazil of the tropics where they really do seem out of place!

I hope that you make it to southern Chile, the main region of German settlement. And If you do get there, I hope that you produce some articles for your blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wearing lederhosen in that climate has got to require a whole lot of talcum powder, although perhaps it encourages yodeling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very good text about southern Brazil. But, in order to make justice, the wine region has award-winning wines. Of course, you have to find at right places. Regards…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind comment. Yes, my generalisation about the quality of the local wines is probably unfair as they certainly do vary in quality. I know that sparkling wines, in particular, are often good or even very good. But my experience is that the “best” (non-sparkling) wine from the Vale Vinhedos remains no match to even mediocre Argentine wines. I only recall tasting one truly superb Brazilian wine – and it wasn’t in Rio Grande do Sul but a wine produced by Villa Francioni, near São Joaquim, in the highlands of Santa Catarina. But I must return to to Rio Grande do Sul and try again…..

LikeLiked by 1 person