Last month I was at the British Library looking at documents in the collection of the India Office, the former British government department that oversaw the administration of the Raj. I was searching for material on Indian migrants in Brazil, an admittedly small topic, but not an entirely insignificant one. In the early 20th century, most British Indians in the Americas (with the notable exception of the Caribbean islands and the Guianas), were Punjabi Sikhs, and amongst them were independence activists from the pro-socialist Ghadr Party. Wherever they were, British officials – including consular officials in Brazil – kept a watchful eye on their activities.

The files I identified were bound with ones on other subjects of concern to the India Office’s Public and Judicial Department. As Brazil-related documents were, unfortunately, few and far between, my attention easily drifted towards the plight of Indian migrants elsewhere in the world.

I skim-read lengthy reports on the Argentine government’s racially motivated hostility towards Sikhs and British consular officials’ attempts to help Indians who were stranded penniless in Buenos Aires to find work or organise onward transport. There were detailed despatches concerning “coolies” on sugar plantations in Suriname, Trinidad and Fiji, all places that were reliant on migrant indentured labour. Individuals and small parties of Indians also absorbed consular attention. Diplomats sent letters to London and Delhi about British Indians in the French Caribbean island of Guadeloupe who were seeking to travel to Mexico, about parties of Indians who were refused permission to land in New Zealand and on efforts to assist destitute Indians in far-flung ports, such as Shanghai, Valparaiso, Marseilles and New York. Although such Indians were typically regarded as an embarrassment and a nuisance, they were still awarded consular assistance, if only to get these British subjects off the streets and away from the attention of the foreign public.

While Indians abroad were usually the subjects being reported, occasionally it was Europeans in India who were being discussed. Most notably there was the issue of Russian exiles who, in the wake of the 1917 Revolution, had made their way across central Asia to find refuge in India. In addition, there was a steady stream of tales concerning orphaned English children, with their carers seeking help to contact family back in Britain.

While all these reports were interesting distractions, it was a short telegram that somehow caught my imagination. A one-page message, dated 17th August 1921, from the office of the Governor of Bengal in Calcutta (present-day Kolkata) to the Secretary of State for India in London, outlined the plight of a young Englishwoman who had been abandoned and was in the process of being deported back to London.

In itself, the telegram reveals little. In April 1920 the then 23-year-old Mrs Ali had arrived in India with (or perhaps to join) her husband, Muhammad. The couple had presumably met in London and on 27th August 1919 they married at Stepney, in the heart of the city’s poor and crowded East End, and Mrs Ali converted to Islam. At some point between April and August 1920, Mr and Mrs Ali separated, he being unable or unwilling to support his wife.

When people think of the British in India, it tends to be of a middle-class society with aristocratic pretensions, an image reinforced by novels, films and television productions such as Passage to India, The Jewel in the Crown, Indian Summers. The reality was far more varied, with about half of the British in India considered to be “low Europeans” (“poor whites”, in other colonial contexts). Amongst these were low-ranking soldiers, seafarers and semi-skilled workers, often employed by railways, port and utility companies. While some would have been joined by British wives, there was a considerable gender imbalance, a consequence of which was the emergence of Eurasian (later termed Anglo-Indian) communities in many parts of the Indian subcontinent.

In the 17th to early 19th centuries, mixed European and Indian relationships – even marriages – were quite common. As the 19th century progressed, such unions became increasingly frowned upon by the colonial authorities and were unusual, except for some outlying parts of the Raj, most notably Burma. The children who resulted were rarely fully accepted into British society nor taken in by their mothers’ families. Even so, compared to most native Indians, these Eurasians (or Anglo-Indians, as they eventually were termed) at least had an elevated place in society. Distinct institutions (schools, orphanages, societies and clubs) emerged to cater to them and Eurasians came to be associated with railway, customs and post office jobs, as well as the nursing and teaching professions.

It was not then Mrs Ali’s working-class origins that would have marked her out as being an oddity in Calcutta, nor was a relationship between a white person and an Indian particularly unusual. Instead the problem was one of gender. Under the British Raj, the few European women who married Indian men would have been shunned by British society. If they were fortunate, such women relied on their husbands’ local support network, or else they were socially completely isolated. Furthermore, any children who resulted from mixed marriages were not accepted socially or legally as members of the Eurasian community, for whom a male European line was the crucial marker.

While “low Europeans” played important roles in British India, the country was not regarded by the British as a land of immigration in the way places like Canada and New Zealand were. The prestige of Britishness was vital for the imperial authorities. As such, Europeans without means to support themselves were not tolerated. From 1869, the European Vagrancy Act gave magistrates in India the power arrest beggars, and other destitute individuals, of European origin and transport them at public expense to Britain or to Australia.

Whereas vagrant European men were considered humiliating to the highly class-conscious white elite, destitute European women were an even greater reason for embarrassment. The great fear was that they would be lured into prostitution; with European men this would be bad enough, but the possibility of Indian men using their services was considered utterly abhorrent to the British mindset. Mrs Ali – simply due to her short-lived marriage to an Indian man – is likely to have been considered to be a degenerate by the authorities and by the wider British community. Other young English women might have been assisted to find suitable work locally, but Mrs Ali would surely have been considered as being beyond redemption. What’s more, the Governor of Bengal’s telegram referred to Mrs Ali as “alias Mrs Campbell”, perhaps being taken by the authorities as indication of loose moral standards. (It is very possible that the former “Mrs Campbell” was a widow – perhaps having lost her first husband in the recently concluded “Great War” – or the title of “Mrs” might simply have been a clerical error.)

Regardless of whether or not Mrs Ali wanted to return to England, by law the choice was not hers. On 10th August 1921 she boarded a P&O passenger steamer, the S.S. Nellore, bound for the port of Tilbury (just outside of London), calling at Colombo and Port Said. It appears that she was expected to go to her father’s home in “Fenton Street” (in reality Fenton’s Avenue), in the east London suburb of Plaistow. Whether Mrs Ali in fact went there was of no interest to the Indian authorities in either Calcutta or London, their sole concern being to remove her from Bengal.

It’s impossible to know what ultimately became of Mrs Ali. As neither Mrs Ali’s birth name, nor the name of her father, are stated in the telegram, and since London marriage registrations for August 1919 do not reveal any individuals whose names might be related to this story, her life remains a mystery. (It is possible that Mr Ali and the former Mrs Campbell simply had a Muslim marriage ceremony that went unrecorded by the civil authorities.) If the young woman did go to Plaistow, did her father take her in? Did she remain a Muslim? What lasting impact did the marriage and her time in India have on her?

In the early 20th century mixed marriages in London were unusual events, but they were not completely unknown ones. At that time, the East End of London (especially the docklands areas) had a small, but not insignificant, Indian minority, largely consisting of Muslims seafarers from Bengal. These men were the foundation of today’s Bengali community, who now make up almost half of the population of Stepney, the place where Mr Ali and Mrs Campbell married each other. Today a marriage such as theirs would go largely unnoticed.

Update

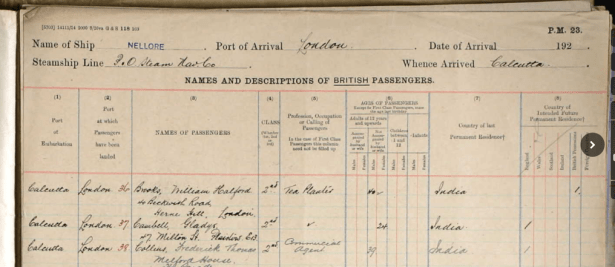

Since publishing this blog post, I have examined the Passenger List for the S.S. Nellore – the ship on which Mrs Ali returned to England in August/September 1921. A matching 24 year old female passenger is listed under the surname of “Cambell” (clearly a spelling error), and two new pieces of information are given. It is now clear that the first name of Mrs Ali/Campbell was “Gladys”.

What has become even more unclear is where Gladys Campbell (or Gladys Ali) went after returned to London. The India Office file indicated that she would be going to her father’s home at 16 Fenton’s Avenue, whereas the Passenger List states an altogether different destination in Plaistow – 47 Milton Street, an address that no longer exists. It is a mystery as to whose home this was and whether Gladys actually went there.

Very interesting post, Oliver.

” Nothing is know of character” Now we are blessed with a sort of chaotic internet archive, which sometimes preserves records of arrests and convictions, even displaying the police photos. If she were alive today, Mrs. Ali’s deportation might be listed, or an arrest for vagrancy, and I think some of the sites solicit payments, to have the listing and pictures removed – – a sort of extortion racket as far as I can see. I hope the rest of her story was a happier one.

You’ve probably thought of this already, but the 1911 census might provide the family name, if you wanted to continue investigating the story. I took a quick glance, and Plaistow appears to have 61 enumeration districts, but if you can figure out which one Fenton’s Ave belongs to, it might provide the surname associated with #16.

Man, the countless stories and mysteries that must be contained in the British Library!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your thoughtful comment – as yours always are!

I did look at the 1911 census returns for 16 Fenton’s Avenue but I didn’t find a 13/14-ish year old girl listed as living there at that time. Even if that was her family’s address, she might, of course, not have been living there at the time. The adults, however, who are listed seem much too old or too young to be her parents. With neither marriage nor census records revealing anything, the English side of the story will remain a mystery – at least until 2021 when the 1921 census returns will be open.

I guess that it’s possible that in Kolkata there might exist records of the court proceedings that resulted in the deportation of Mrs Ali/Campbell. If this is the case, I somehow doubt that they are at all accessible!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, leaving a bit of mystery, we can invent our own endings. I’m wishing her a happy one! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post, Oliver. I’ve enjoyed reading it all, but the gender aspect was particularly interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Graça!

LikeLike

An eye opener/ The British can be blamed for everything that is wrong with present day society/Snobbery/racism/elitism and slavery encouragement to boot/Wherever they ruled there have been acts against the very morals of such society/It is extremely gratifying that their once proud slogan Britannia rules the Waves is no more and they have been relegated to a Country of No Consequence/The Indians/Pakistanis/Irish to name a few societies can attest to their wrongdoings through the ages/India in particular has a whole new take on British rule with their schemes/plundering and what not a constant reminder of an unholy OCCUPATION

LikeLike

I tend to agree with you! 🙂

LikeLike

Very interesting story and reflections, Oliver. Really gets under the skin of colonialism, in a very vivid and personal way. Wondering how much material there is on Indian migrants of Portuguese origin in Brazil. Possibly quite a lot. Incidentally, recently found myself in the “I.C. Colony” in the north Mumbai district of Borivili- the Immaculate Conception Colony, that is, which has a high concentration of Roman Catholics. The church of the Immaculate Conception seems to date back to the 16th century, and going by the graveyard, the huge daily congregation and the local business names, I reckon the local population must still be heavily of Portuguese origin. This is, I think, in contrast to the other very Christian enclave in Mumbai – Bandra – which seems to be much more Anglican and of British provenance. The novelist Amit Chaudhuri talks from time to time about moving there as a child and being sent to an Anglican school on St Cyril’s Road. But presumably there was lots of well-recorded migrant traffic between Brazil and Goa, Daman and Diu, Mangalore and Cochin, and possibly old Bombay, at various times. Amitav Ghosh’s In An Antique Land has an interesting section on Mangalore’s even earlier, 12th century, importance, albeit at that point as a link with the Middle East not Brazil!

LikeLike

Thanks, Nick, for your thoughts. Given that Brazil was a vital stopping off point for ships travelling between Portugal and the East Indies, I assume that there some Indians would have settled in colonial Brazil during the 16th and (especially) the 17th century – but I can’t recall having seen anything on this. There were definite efforts in the late 18th and early 19th centuries by the Portuguese to bring Chinese to Brazil – to experiment with tea planting in Rio, to work as miners and craftsmen (traces of their work can still be seen on some buildings in Diamantina). More recently, quite a lot of former Goans fled Mozambique following independence in the 1970s and settled in Brazil. Otherwise, most Indians in Brazil came from British India – in the mid- and late 19th century there were a couple of fairly significant attempts to introduce (from Mauritius!) Indian labourers to Rio sugar plantations. I’ve also heard that there are quite a few Sindhi traders in Manaus – I think that most of them have links with Panama.

LikeLike